A Simple Model of Government

Looking into the black box of government is cool and fun.

Note: This is Part 2 of a three-part series. Our ultimate goal is to understand the critical role of citizenship in a free and flourishing civilization (Part 3). To do that, we need to understand government as an organization (Part 2 - you are here). To do that, we need to understand organizations in general (Part 1).

The Black Box

The word “government” makes our brain do weird things. It triggers strong emotions1 and puts us on guard. How could it not? The stakes are high - government is the source of our problems and the only solution and the bad guys are this close to taking over the whole thing. More charitably, it’s a proxy for our societal values and we understandably want our government to reflect them.

But when we get worked up about government, who are we really yelling at? Despite all the emotion and attention it gets, we treat government like a black box. It feels “other” to us, like a distant, shadowy machine dedicated to making the world bad. We’re so poisoned by cultural forces like the anti-politics meme and the government anti-meme that we don’t dare to look in and we mostly don’t even realize we should.

I would argue that part of the reason we react to “politics” and “government” in such emotional terms is because we actually aren’t even able to think about it rationally. It’s hard to reason about a black box.

So what is government? It’s an institution, and we know how to think about those.

Government, Our Favorite Institution <3

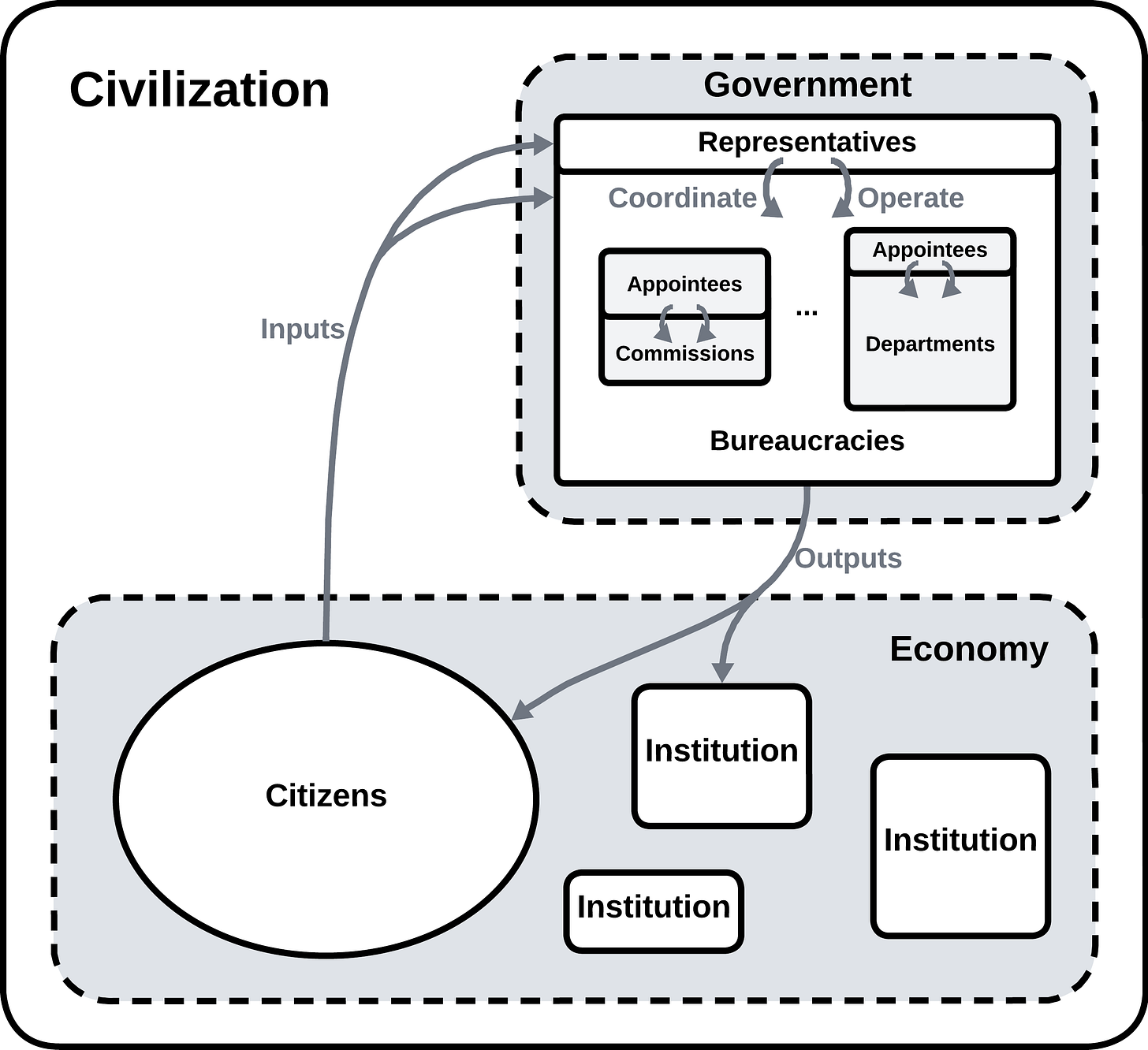

In Part 1 we argued that institutions are an especially important kind of organization because of their influence on the shape of civilization. We also established a simple framework for thinking about the structure (purpose, agents, bureaucracies) and function (inputs, outputs, coordination, operation) of organizations and then used this frame to set up an analysis of any organization by asking four important analysis questions.

Here in Part 2, we’ll use these tools to look closely at the structure and function of government which will ultimately allow us to replace the black box with a simple model of government. This simple model will then guide us in learning about the full complexity of government.

Government: Structure

Purpose: In the most fundamental sense, the purpose of government is to solve coordination problems for civilization which means enabling and constraining the many actions and interactions going on out there in civilization.2 Governments have attempted to do this in wildly different ways. Self-governing societies must be explicit about the purpose of government, which they capture in their foundational documents. When the states ratified the US Constitution, that was basically the citizens agreeing to the purpose of the federal government.

As a citizen of San Francisco, I’m subject to a hierarchy of laws within the US system of federated government. The federal, state, and local governments define their purpose in the US Constitution, the California Constitution, and the San Francisco City Charter respectively.3 Zooming in on the local level, the charter describes the purpose of the city government in the preamble:

In order to obtain the full benefit of home rule granted by the Constitution of the State of California; to improve the quality of urban life; to encourage the participation of all persons and all sectors in the affairs of the City and County; to enable municipal government to meet the needs of the people effectively and efficiently; to provide for accountability and ethics in public service; to foster social harmony and cohesion; and to assure equality of opportunity for every resident: We, the people of the City and County of San Francisco, ordain and establish this Charter as the fundamental law of the City and County.

Agents: In government, the top level agents are the elected representatives. They appoint other agents underneath them in the institutional hierarchy and delegate the authority to oversee particular elements of the bureaucracy.

In San Francisco, we elect the Mayor who serves as the chief executive. The Mayor then appoints commissioners to oversight commissions and directors to various departments. For instance, the Mayor appoints 4 of the 7 members of the Police Commission who oversee the Police Department. The Mayor also selects the Chief of Police, who is the agent at the top of the Police Department.

Bureaucracies: For governments, these are the many departments and agencies that implement and execute the services of government as dictated by the purpose under the management of the agents.

In San Francisco, this includes boots-on-the-ground entities like the Police Department. Police officers must follow the policies and procedures created by agents like the Mayor, Police Commission, and Chief of Police.

Government: Function

Receive Inputs: In a self-governing system, the fundamental input is the nebulous “will of the people” which is primarily signaled through voting and accompanied by the resources needed to execute that will. Entities within government may also provide inputs to each other.

Citizens provide input to government in a variety of ways. In San Francisco, we can vote to elect representatives, vote to approve/reject ballot propositions, provide public comment at hearings, join advisory boards, file appeals, and more! We

canmust also provide lots of tax dollars. Of course, representatives themselves are an input to government.The logic is similar internally. A mayoral appointment to the Police Commission is an input.

Coordination: Compared to private institutions, governments must be much more transparent about how they allocate power internally. For this reason, the most important coordination decisions are formalized in their constitutional documents. From within those constraints, agents then have authority to configure the bureaucracies to help carry out their will. Incoming elected officials will often create/arrange entities.

In San Francisco, the city charter formalizes the hierarchical relationship between the Mayor, Police Commission, and Police Department. As such, neither the Mayor nor any other government agent can alter these dynamics without the voters approving a charter amendment. However, the Mayor can use an executive directive to restructure authority and oversight responsibilities with respect to the city’s housing development plan.

Operation: This is how governments turn the will of the people (inputs) into civilizational coordination or “governance” (outputs). Because of our cultural and legal emphasis on the rule of law, our governments are much more constrained by process than private institutions. This focus on formalization and procedure means that operations are highly bureaucratized.4 As a result, the overall effectiveness of government is highly dependent on the effectiveness of the bureaucracies. This is influenced by several factors, like the quality of coordination in the broader org structure. It also depends on the competence of agents in adding/modifying/deleting work processes (changing the bureaucracy) based on performance, and the quality of the bureaucrats and the technology systems supporting them.

How does San Francisco turn resource inputs like tax dollars and informational inputs like 911 calls into outputs like “peace” and “public safety” via law enforcement? Operational procedures for law enforcement are primarily established by the Police Commission. They determine things like how SFPD officers make traffic stops and which software they use. These policies are then implemented in the Police Department by the Chief of Police and ultimately executed by police officers and their supporting apparatus like dispatchers.

Export Outputs: We said the fundamental purpose of government is to coordinate civilization, so the fundamental output is coordination.5 The governmental outputs that achieve this coordination take many forms, tangible (infrastructure, public services, etc) and intangible (health, education, safety, etc).

In SF, the output of a 911 call might be an SFPD officer arriving at the scene of a crime to gather information and start an investigation. How reliably this tangible output occurs can influence the more intangible feeling of safety.

By pulling out a few essential features and adding some simple visualizations, we’ve already started to unwind the complexity that can cloud our understanding. It should already be clear that government is only a black box if we choose not to look.

A Simple Model of Government

To arrive at our model of government, we must situate the institution in the context of civilization. This means we need to think clearly about civilization too. Easy! A few definitions just to keep things in order:

Civilization - The full picture. All of us, our interactions, the environment we live in, and the world we build. This is what we want to flourish, so we study orgs to better grasp its shape.

Government - You know all about this by now!

Economy - Much more than just business, we mean human action and interaction as individuals and organizations.6

Citizens - That’s you!

Look at that, the whole world in just a few boxes and arrows. Very convenient. But how can we actually use these tastefully arranged shapes? As a starting point. We’ve replaced the black box with some mental infrastructure we can build on. Government is truly a complex institution and there’s a lot to learn. With a rough model to anchor our thinking, we know what to look for and which questions to ask.

In the last section, I’ll show how this mode of thinking helped me sidestep chaotic debates to get right at the structural and dynamic causes of problems in my local government.

How to Learn About Government

In San Francisco, public safety is a popular topic. Though it’s a one-party (Democrat) city, there are two main factions - “progressives” and “moderates”. Naturally, both are unhappy with the state of public safety, but for different reasons. Our approach is useful to both, but dependent on neither. Our model of government and our tools for organizational analysis are nonpartisan; they work for anyone who wants to understand their government.

Until recently, I knew almost nothing about how “public safety” was produced by my government. Angry twitter X threads highlighted bits and pieces but I still couldn’t really explain what was going on. Guided by a more productive systems perspective, I was able to learn. Let’s follow the process to see how it works. If you’ve been paying attention so far you’ll recognize these names, but I didn’t know them when I was first starting. Let’s learn about government:

Most systems analysis, especially government, starts by noticing an undesirable output - something that doesn’t seem right. In my case, no one seems happy with the state of public safety in SF. We might be ready to declare that this thing is not doing what it's supposed to do but that assumption is just the beginning of the process.

This leads us to Question 1 - What is this thing supposed to do? We don’t need to overthink this; the city government is obviously supposed to maintain public safety. For confirmation, the city charter states:

The Police Department shall preserve the public peace, prevent and detect crime, and protect the rights of persons and property by enforcing the laws of the United States, the State of California, and the City and County.”

Fair enough. So the output of public safety is clearly not fulfilling the purpose of the gov/SFPD.

So, Question 2 - Who is in charge here? Almost time to start pointing fingers. The two entities I knew had to be involved were the Mayor, as the boss of the city, and the Police Department, as the folks who do law enforcement. This seems to be where most people end their analysis.

But I like to do high-conviction finger pointing, so I needed to know what they were doing wrong specifically. This means I had to learn more about their authority and responsibility which brings us to Question 3 - What authority do they actually have? I did some searching about what authority the Mayor has over the Police Department (SFPD), but found that another entity - the Police Commission (SFPC) - seems to have most of the authority over how policing works in the city. Here we see the recursive nature of systems/org analysis - I found new agents!

So I had to update my list of relevant agents. The Police Commission document also mentioned the Chief of Police which sounded important. Now my mental model of government with respect to public safety in SF includes the Mayor, the Police Commission, the Chief of Police, and the Police Department.

It wasn’t yet clear how this really works, so I turned to the charter to read up on their respective authority and responsibilities. I found that the Mayor appoints the majority of commissioners to the SFPC, but doesn’t seem to have much direct influence on law enforcement. The SFPC seems to effectively have control of the SFPD because they have broad authority to set policies for law enforcement: they can impose discipline on SFPD officers, they approve the SFPD budget, and they can even remove the Chief of Police! As the director of the Police Department, the Chief of Police primarily implements and oversees the policies set by the SFPC.

I was starting to get a good feel for where agency lives in the system. Now on to Question 4 - How is that agency being used? The SFPC stands out as the most influential entity so that was my primary focus. But I was still confused because the Mayor had recently made statements blaming the SFPC for public safety issues even though she appoints the majority of the members. If she appoints a controlling share of the commission, why is she mad at her own people? I took a closer look and found something very interesting. The Board of Supervisors appoints the other 3 members of the commission. But there’s more to the story. The Board must also approve commissioners nominated by the Mayor. So in a roundabout way, the Board of Supervisors has subtle control over the Police Commission. It’s clear that the current Mayor and the current Board of Supervisors do not get along, so I can start to see the problem here.

In conclusion, what started as “Why hasn’t the Mayor/SFPD stopped crime in SF!?” was completely reframed as a systems investigation which revealed that a charter amendment diluted the authority of the Mayor to appoint police commissioners, which means she doesn’t really have the authority to change law enforcement policy unless she can get a majority of the Board members on her side.

This mode of thinking is much less emotional and much more productive since it lets us directly uncover organizational problems and sets the context for finding solutions. As we’ve hopefully conveyed, this approach also lends itself well to visualization.

Of course this is just one example, but that’s the point. Once you have a simple model of government, you can build on it in any direction that interests you because the skill we’re actually learning is complex systems analysis.

In Part 3, we will use this model to examine the role of citizenship with respect to government and the greater orchestration of civilization.

You might argue that “apathy” is a common feeling toward government, but apathy is just a strong emotion wrapped in the blanket of nihilism.

Coordination is essential for the maintenance of complex systems. Government can help us overcome Molochian dynamics which represent some of the greatest dangers to civilization.

The Charter is not truly constitutional in the legal sense, but it does define the purpose of the city and county of San Francisco. See hierarchy of laws for more info.

Bureaucratization is often but not necessarily bad. Like all engineering decisions, it’s a tradeoff. In this case, it includes considerations like responsiveness and flexibility vs repeatability and reliability.

This is not altogether different from the internal coordination function defined in our model of organization. The difference is that this coordination is directed externally to civilization and achieved via outputs like goods, services, and laws.

Systems scientists would call this “metabolism” which is more accurate, but I didn’t want to weird you out.